Georges Seurat

(1859 - Paris - 1891)

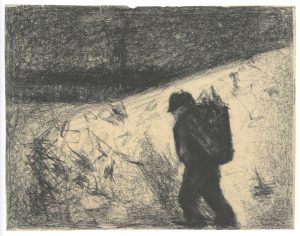

La Zone (Filette dans la neige, La Grève), 1883

Conté crayon on Michallet paper, 24.1 x 30.5 cm

Provenance:

Léon Appert (1837-1925), the artist's brother-in-law, Paris

Possibly by descent to Maurice Appert, the artist’s nephew, Paris[1]

Galerie Knoedler & Co., Paris

Galerie Gérard Frères, Paris

Gustave Goubaux

Félix Fénéon, Paris, 1947

Paris, Hôtel Drouot, Catalogue de la collection Félix Fénéon, 2e vente, 30.5.1947, lot 40

Alex Loeb, Paris, 1962

Galerie Max Kaganovitch, Paris, 1966

Nehama Jaglom, New York (acquired from the above)

By descent to private collection, New York

New York, Sotheby's, auction sale, 3 May 2005, lot 48

Purchased at the above sale by the present owner

Exhibited:

Aquarelles, pastels et dessins des Maitres du XIXe siècle, Paris, Galerie Georges Aubry, 1931, no. 75 (titled La Grève)

Georges Seurat, Paris, Galerie Paul Rosenberg, 1936, no. 102

Seurat and his Contemporaries, London, Wildenstein Galleries, 1937, no. 67

Le Néo-Impressionnisme, Zurich, Galerie Aktuaryus, 1937, no. 13

Artists who died young, London, Leicester Galleries, 1938, no. 31

Le dessin de Toulouse-Lautrec aux Cubistes, Paris, Musée national d'Art Moderne, 1954, no. 191

Les 30 ans de la galerie: Dessins, aquarelles, tableaux, sculptures des XIXe et XXe siècles, Paris, Galerie Max Kaganovitch, 1966

Georges Seurat, The Drawings, New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 2007-8, no. 62, repr. in color

Literature:

Gotthard Jedlicka, 'Die Zeichnungen Seurats', in Galerie und Sammler, Zurich, October-November 1937, repr. p. 149

George Seligman, The Drawings of Georges Seurat, New York 1947, no. 32, pp. 23 & 68

Cesar de Hauke, Seurat et son œuvre, II, Paris, 1961, no. 521, repr. p. 115

Robert Herbert, Seurat’s Drawings, New York 1962, no. 165, p. 186André Chastel and Fiorella Minervino, Tout l'œuvre peint de Seurat, Paris 1973, no. D128, repr. p. 114 (titled Fillette sur une Plage. Le Port)

‘Where nothing ends and nothing begins, where people are the flotsam of social misfortune’ (‘the Zone’ as described by Octave Mirbeau)[2]

The following text is an extract from Jodi Hauptmann’s catalogue writings on La Zone and on Seurat’s draftsmanship in Georges Seurat, The Drawings, exhib. cat., MOMA, New York 2007.

With their growing and shifting populations, volatile class structure, and mutating geography, the areas immediately surrounding the city’s fortifications, the undeveloped waste ground outside the walls known as ‘the Zone’, and suburbs like Courbevoie, Asnières and Saint-Denis stood for, in the eyes of politicians, sociologists, criminologists, artists, and writers alike, a geographic and social unease.[3]

Let us think of la fillette – the young girl – as a spectator surveying the grand desolation that is the Zone. What does she see? A snowy hill cascading into a darkness that resembles murky water (perhaps the ditch surrounding the fortifications); a horizontal footpath cutting across the foreground; a town in the distance with structures reaching for the sky; vapors rising from the village; jagged lines familiar from Le chiffonnier (1882-3) The Ragpicker (Fig. 1) resembling desiccated brush or debris; a dark, ominous sky.[4]

Fig. 1 Georges Seurat, Le chiffonnier, conté crayon on Michallet paper, 23.5 x 31.1 cm, 1882-3, private collection

It is clear that the striking characteristics of Seurat’s drawings – the dramatic play of light and dark, subjects that simultaneously coalesce and dissipate, the tension between a gridded scrim and a picture – emerge from the relationship, the tension between Michallet paper and conté crayon. Very early on, Seurat brought together these two materials and exploited the texture of this particular paper. While we derive enormous visual pleasure from the material presence of these drawings, how we read their subject matter and meaning depends almost entirely on absence. In contrast to Seurat’s most famous paintings, his drawings present empty places and lone figures. They are moody to a point of melancholy. Seurat’s silence is, in fact, an aesthetic. His figures are self-involved – in work, reverie, or sleep. Practically all of his isolated figures turn their back to the viewer or hide their heads. Without a face or a front, these figures cannot speak. Not simply quiet, these drawings are aggressively silent.[5]

About 270 drawings from Seurat’s mature period, starting c. 1881, are known. Some of these are preparations for his canvases but most are independent drawings, works created on their own, proving that drawing in and of itself was an important activity for the artist. Abandoning the contour line of his training, the artist stroked the conté crayon across the sheet’s ridges, thus devising his own kind of draftsmanship: the emphasis on dark and light tones to abstract and simplify figures; the layering of pigment to create a range of densities, from a translucent scrim to impenetrable darkness; the interlacing of lines to complicate space; the impossibly accurate description of subjects using the barest of means.[6]

[1] For the only mention of this, see Georg Seligmann, The Drawings of Georges Seurat, New York 1947, no. 32, p. 68

[2] Octave Mirbeau, cited in Richard Thomson, Seurat, Oxford 1985, p.56.

[3] Jodi Hauptmann in Georges Seurat, The Drawings, exhib. cat., New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 2007-08, p. 108.

[4] Ibid., p. 117.

[5] Ibid., p. 13.

[6] Ibid., p. 10.