Two Works based on the Photograph of Le Joueur d’orgue barbarie:

Charles Nègre

(1820 - Grasse - 1880)

Le Joueur d’orgue barbarie - The Organ-Grinder, 1853

Oil and red chalk on paper, 22.5 x 16.5 cm

Provenance:

The Nègre family collection

Exhibited:

Real /Ideal: Photography in France 1847-1860, Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 30 August - 27 November 2016

Charles Nègre

(1820 - Grasse - 1880)

Le Joueur d’orgue barbarie - The Organ-Grinder, Paris 1853

Oil over salted paper print from a paper negative, 23.5 x 18 cm

Labelled on the verso Le Joueur d’Orgues / par Charles Nègre / 1853 / Collection Joseph Nègre, No. 6 and Musée Fragonard / Exposition Charles Nègre / 27 juillet - 30 septembre 1963 / No 7 and stamped Société Fragonard - Grasse and La Peinture sous le signe de la / photographie / (Malerei - Fotografie) /Münchner Stadtmuseum / 3-9-70 - 9-11-70 and Kunsthaus Zürich / Ausstellung Malerei und Photographie im Dialog 12.5.-24.7.77 / Charles Nègre / Le Joueur d’Orgues 1853 / Besitzer Joseph Nègre

Provenance:

Joseph Nègre, great-nephew of the artist

The Nègre family collection

Literature:

Françoise Heilbrun, Charles Nègre, 1820-1880, das photographische Werk, Munich 1988, no. 86, p. 106, repr.

Exhibited:

Charles Nègre, Grasse, Musée Fragonard, 27 July-30 September 1963, no. 7

Malerei nach Fotografie: von der Camera obscura bis zur Pop Art; eine Dokumentation, Münchner Stadtmuseum, Munich, 3 September-9 November 1970 (ex-catalogue)

Malerei und Photographie im Dialog von 1840 bis heute, Kunsthaus Zürich, Zurich, 12 May-24 July 1977 (ex-catalogue)

Charles Nègre, Images de la Provence en 1852, Quand la peinture devient photographie, exhib. cat., Fréjus, Villa aurélienne, 16 April-2 July 1995, p. 16

Real /Ideal: Photography in France 1847-1860, Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 30 August - 27 November 2016

These two works by Charles Nègre are unique pieces and are of exceptional rarity. Together, the two works provide deep insights into a creative process generated by the interaction between early photography and contemporary painting in Paris in the 1850s. The process was fuelled by a generation of young artists often working as painters and photographers at the same time, whose objective it was to open up new creative opportunities.

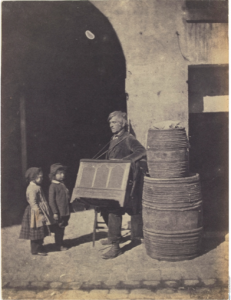

A Nègre motif documents this new creative process in action. The motif is that of a Joueur d’orgue [organ-grinder]. Nègre’s process consists of four separate stages. The first stage is a photograph titled Joueur d’orgue de barbarie of 1852/3. A number of prints of this photograph are preserved (Fig. 1). The second stage, presented here, is a print of the same photograph reworked by Nègre with transparent and opaque layers of oil paint The third stage is a version of the motif in almost identical format painted in oil over a traced outline drawing in red chalk. The fourth stage was almost certainly the painting titled Un joueur d’orgue which Nègre exhibited at the Paris Salon on 15 May 1853. This painting is now presumed lost.

The development process applied to the motif is of interest not just for the fact that it is documented in four stages. It is of key importance because in contrast to traditional working processes – preliminary drawing, oil study, painting – it takes a photograph as its point of departure. And this photograph is remarkable in that contemporary critics recognized it as an autonomous work, attributing to it the same artistic qualities and edifying overtones that could be expected of a history painting.

Nègre was born in Grasse and moved to Paris in 1839. He enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts and took up his studies under the painters Paul Delaroche, Michel Martin Drolling, and, in 1843, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Delaroche was keenly interested in the new techniques of photography. He encouraged his students to take up the medium and to exploit the artistic potentialities of the daguerreotype. Daguerrotypes initially served simply as aide-mémoires, much like sketches made to help the recollection of motifs found in nature and in everyday life. Paris artists were quick to grasp the importance of its greater potential. Compared with the pencil sketch or watercolour the new medium was a time-saver and thus more spontaneous – it could be used to handle complex changes of perspective, to depict figures in staged settings or capture changing views of a subject from different angles. In short, it provided a range of opportunities to vary the desired segment of an image. All this was to contribute to the recognition of photographs as autonomous works of art. Delaroche’s studio would be an important stepping stone in the careers of many leading photographers of the 1850s – Henri Le Secq, Gustave Le Gray, Roger Fenton and Charles Nègre – who were the direct heirs of the generation that had invented the new medium. They came to be known as Les primitifs de photographie.[1]

Nègre began to concentrate on the medium of photography in 1844, at first using the daguerrotype technique but turning to calotype in the late 1840s. Calotype had a number of advantages over the earlier method. A paper negative was used instead of a polished, silvered copper plate. Exposure time was shorter and an unlimited number of prints could be made.

Nègre exhibited his paintings regularly at the Paris Salon in the 1840s and 1850s. At the same time, he was also very active as a photographer. He was a founder member of the Société héliographique in 1851. The club’s members were chiefly photographers and natural scientists.[2] Nègre moved into a studio on the Isle Saint-Louis at 21a Quai Bourbon in 1850. From here, he would set out on exploratory trips through the streets and into the backyards of the city. At first, he was more interested in collecting visual motifs in preparation for paintings but he quickly recognized the extraordinary artistic and commercial potential of photography. It rapidly became his chief focus of interest. He concentrated on motifs drawn from city life, photographing street hawkers, chimney sweeps and musicians, and developed into a master of the genre [of urban life][3] – as his organ-grinder motif demonstrates.[4]

Nègre’s salted paper print of 1852/3 (Fig. 1) was well received by the critics. A review by Ernest Lacan, editor-in-chief of La Lumière, published on 10 September 1853, provides valuable insights into contemporary reaction to Nègre’s photograph. Lacan declared it to be an autonomous work of art and his critical analysis is barely distinguishable from conventional contemporary evaluation of history painting. He notes:

The play of light and shade on the wall behind the organ-grinder, and the looming dark of the deep vault behind him recall the vigour of Decamps’ drawings. The finely drawn features of the old man and his intelligent, pensive, somewhat sad expression, the minute details of his shabby clothing and yellowing velvet jacket, creased and dirty, are based on some of Meissonier’s most meticulous studies. Two children – a small boy and a small girl – […] stand listening, open-mouthed and entranced by the strangeness of the sounds produced by the popular street organ. There is a harrowing contrast between the rigid stance and fascinated concentration of the children – who have seen so little and are astonished by so much – and the world-weariness and resignation of the old street musician – who has seen so much and gained so little, and despite his experience has ended up as a beggar. […] Nègre’s photograph says it all. It is not in any way a record of a chance encounter. It is a brilliantly conceived image, purposefully designed and a forceful statement in itself.[5]

Fig. 1 Charles Nègre, The Organ-Grinder with Two Children Listening, 1852/3, salted paper print from a lost dry waxed paper negative, 20.6 x 15.6 cm, Paris, Musée d'Orsay, inv. PHO 2002 3

Lacan believed that the choice of an organ-grinder as a subject was superior to the choice of a rag-and-bone man or a chimney sweep. Subjects with perceived didactic or moral content – and the organ-grinder was seen in this light – were popular and well-received at the time. These sentiments were shared by contemporary writers. Organ-grinders make frequent appearance in French nineteenth-century literature. Good examples are Henri Murger’s Scènes de la vie de bohème and Baudelaire’s Le spleen de Paris.[6]

On 15 May 1853 Nègre exhibited a small painting titled Un joueur d’orgue at the Paris Salon. Its whereabouts are now unknown. There is, however, every reason to believe that the painting was a direct interpretation of the salt print discussed above. The art critic Henri de Lacretelle lauded the painting in his review of the Salon: [...] the fine colouristic values which his work has long promised [are] united with stylistic audacity and skilful execution [...].[7]

The present two works can be seen as preliminary stages in a process – more specifically, as stages in the development of Nègre’s 1853 Salon painting. They demonstrate how he reworked a photographic model, recording the subject’s gradual evolution from photograph to oil painting. In the first of the two works Nègre uses a salted paper print as his ground and cautiously works over it. His brushwork is transparent in areas where contours and detail are more precisely defined, such as in the facial features, the shoes and the hoops of the cask. In other areas, the paint is applied in opaque layers. The resulting study unites colouristic and graphic approaches, enabling him to investigate the extent to which black and white contrasts could be translated into colour. And he was almost certainly attracted by the range of effects inherent in photography and its varying degrees of precision. An example is the contrast between the sharpness of the organ-grinder’s features and the less sharply focused faces of the children.

In the second of the two works, the photograph no longer serves as a model for the definition of detail. It is used to create a composition made up of areas of colour. In order to do this Nègre transferred the main outlines of the photograph onto paper using red chalk and deploying colour to build up the compositional structure. His focus lies on the play of light and on colouristic effect.

Nègre spent the final fifteen years of his life in Nice. Although a photographer of considerable fame, he never stopped painting. His pioneering work in the field of photography began to be rediscovered in the 1960s. Multiple exhibitions in Europe and the United States followed.

[1] The term primitifs was coined by Nadar. See French primitive photography, exhib. cat., Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia 1969.

[2] The Société héliographique was the world’s oldest association of its kind. In 1854 it was reconfigured as the Société française de photographie, with Nègre as one of its members. The association is still active today. It holds a print of Nègre’s Joueur d’orgue[organ-grinder] in its collection.

[3] Heilbronn, op. cit., p. 7.

[4] Nègre quickly went on to other motifs and also produced portrait photographs, studies of nudes, landscapes and photographs of historic monuments in addition to genre subjects.

[5] Ernest Lacan, La Lumière, Paris, 10 September 1853, 13/37, p. 147; adapted from James Borcoman’s trans. in Charles Nègre 1820-1880, exhib. cat., Ottawa, the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa 1976, p. 29.

[6] See André Jammes, Charles Nègre Photographe 1820-1880, exhib. cat., Arles, Musée Réattu and Paris, Musée du Luxembourg, pp. 75-6.

[7] Henri de Lacretelle, ‘Salon de 1853 ’, in La Lumière, Paris, 16 July 1853, 13/29, p. 113.